Tacoma Narrows Bridge (1940)

| Tacoma Narrows Bridge | |

|---|---|

The original Tacoma Narrows Bridge roadway twisted and vibrated violently under 40-mile-per-hour (64 km/h) winds on the day of the collapse |

|

| Other name(s) | Galloping Gertie |

| Design | Suspension |

| Total length | 5,939 feet (1,810.2 m) |

| Longest span | 2,800 feet (853.4 m) |

| Clearance below | 195 feet (59.4 m) |

| Opened | July 1, 1940 |

| Collapsed | November 7, 1940 |

|

|

|

The 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge was the first incarnation of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, a suspension bridge in the U.S. state of Washington that spanned the Tacoma Narrows strait of Puget Sound between Tacoma and the Kitsap Peninsula. It opened to traffic on July 1, 1940, and dramatically collapsed into Puget Sound on November 7 of the same year. At the time of its construction (and its destruction), the bridge was the third longest suspension bridge in the world in terms of main span length, behind the Golden Gate Bridge and the George Washington Bridge.

Construction on the bridge began in September 1938. From the time the deck was built, it began to move vertically in windy conditions, which led to construction workers giving the bridge the nickname Galloping Gertie. The motion was observed even when the bridge opened to the public. Several measures aimed at stopping the motion were ineffective, and the bridge's main span finally collapsed under 40-mile-per-hour (64 km/h) wind conditions the morning of November 7, 1940.

Following the collapse, the United States' involvement in World War II delayed plans to replace the bridge. The portions of the bridge still standing after the collapse, including the towers and cables, were dismantled and sold as scrap metal. Nearly 10 years after the bridge collapsed, a new Tacoma Narrows Bridge opened in the same location, using the original bridge's tower pedestals and cable anchorages. The portion of the bridge that fell into the water now serves as an artificial reef.

The bridge's collapse had a lasting effect on science and engineering. In many physics textbooks, the event is presented as an example of elementary forced resonance with the wind providing an external periodic frequency that matched the natural structural frequency, though its actual cause of failure was aeroelastic flutter.[1] Its failure also boosted research in the field of bridge aerodynamics-aeroelastics, the study of which has influenced the designs of all the world's great long-span bridges built since 1940.

Contents |

Design and construction

The desire for the construction of a bridge between Tacoma and the Kitsap Peninsula dates back to 1889 with a Northern Pacific Railway proposal for a trestle, but concerted efforts began in the mid-1920s. The Tacoma Chamber of Commerce began campaigning and funding studies in 1923. Several noted bridge engineers, including Joseph B. Strauss, who went on to be chief engineer of the Golden Gate Bridge, and David B. Steinman, who went on to design the Mackinac Bridge, were consulted. Steinman made several Chamber-funded visits, culminating in a preliminary proposal presented in 1929, but by 1931, the Chamber decided to cancel the agreement on the grounds that Steinman was not sufficiently active in working to obtain financing. Another problem with financing the first bridge was buying out the ferry contract from a private firm running service on the Narrows at the time.

The Washington State legislature created the Washington State Toll Bridge Authority and appropriated $5,000 to study the request by Tacoma and Pierce County for a bridge over the Narrows.

From the start, financing of the bridge was a problem: revenue from the proposed tolls would not be enough to cover construction costs, but there was strong support for the bridge from the U.S. Navy, which operated the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, and from the U.S. Army, which ran McChord Field and Fort Lewis near Tacoma.

Washington State engineer Clark Eldridge produced a preliminary tried-and-true conventional suspension bridge design, and the Washington Toll Bridge Authority requested $11 million from the Federal Public Works Administration (PWA). Preliminary construction plans by the Washington Department of Highways had called for a set of 25-foot-deep (7.6 m) girders to sit beneath the roadway and stiffen it.

However, according to Eldridge, "Eastern consulting engineers" - by which Eldridge meant Leon Moisseiff, the noted New York bridge engineer who served as designer and consultant engineer for the Golden Gate Bridge - petitioned the PWA and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to build the bridge for less. Moisseiff proposed shallower supports—girders 8 feet (2.4 m) deep. His approach meant a slimmer, more elegant design, and also reduced the construction costs as compared with the Highway Department's design. Moisseiff's design won out, inasmuch as the other proposal was considered to be too expensive. On June 23, 1938, the PWA approved nearly $6 million for the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. Another $1.6 million was to be collected from tolls to cover the estimated total $8 million cost.

Following Moisseiff's design, bridge construction began on September 27, 1938. Construction took only nineteen months, at a cost of $6.4 million, which was financed by the grant from the PWA and a loan from the RFC. The Tacoma Narrows Bridge, with a main span of 2,800 feet (850 m), was the third-longest suspension bridge in the world at that time, following the George Washington Bridge between New Jersey and New York City, and the Golden Gate Bridge, just north of San Francisco.[2] Moisseiff and Fred Lienhard, the latter a Port of New York Authority engineer, published a paper[3] that was probably the most important theoretical advance in the bridge engineering field of the decade.[4] Their theory of elastic distribution extended the deflection theory that was originally devised by the Austrian engineer Josef Melan to horizontal bending under static wind load. They showed that the stiffness of the main cables (via the suspenders) would absorb up to one-half of the static wind pressure pushing a suspended structure laterally. This energy would then be transmitted to the anchorages and towers.[4]

Using this theory, Moisseiff argued for stiffening the bridge with a set of eight-foot-deep plate girders rather than the 25 feet (7.6 m)-deep trusses proposed by the Washington Toll Bridge Authority. This change was a substantial contributor to the difference in the projected costs of the designs.

Because planners expected fairly light traffic volumes, the bridge was designed with two lanes, and it was just 39 feet (12 m) wide. This was quite narrow, especially in comparison with its length. With only the 8 feet (2.4 m)-deep plate girders providing additional depth, the bridge's roadway section was also shallow.

The decision to use such shallow and narrow girders proved to be the original Tacoma Narrows Bridge's undoing. With such minimal girders, the deck of the bridge was insufficiently rigid and was easily moved about by winds; from the start, the bridge became infamous for its movement. A mild to moderate wind could cause alternate halves of the center span to visibly rise and fall several feet over four- to five-second intervals. This flexibility was experienced by the builders and workmen during construction, which led some of the workers to christen the bridge "Galloping Gertie." The nickname soon stuck, and even the public (when the toll-paid traffic started) felt these motions on the day that the bridge opened on July 1, 1940.

Attempt to control structural vibration

Since the structure experienced considerable vertical oscillations while it was still under construction, several strategies were used to reduce the motion of the bridge. They included[5]

- attachment of tie-down cables to the plate girders, which were anchored to 50-ton concrete blocks on the shore. This measure proved ineffective, as the cables snapped shortly after installation.

- addition of a pair of inclined cable stays that connected the main cables to the bridge deck at mid-span. These remained in place until the collapse, but were also ineffective at reducing the oscillations.

- finally, the structure was equipped with hydraulic buffers installed between the towers and the floor system of the deck to damp longitudinal motion of the main span. The effectiveness of the hydraulic dampers was nullified, however, because the seals of the units were damaged when the bridge was sand-blasted before being painted.

The Washington Toll Bridge Authority hired Professor Frederick Burt Farquharson, an engineering professor at the University of Washington, to make wind-tunnel tests and recommend solutions in order to reduce the oscillations of the bridge. Professor Farquharson and his students built a 1:200-scale model of the bridge and a 1:20-scale model of a section of the deck. The first studies concluded on November 2, 1940—five days before the bridge collapse on November 7. He proposed two solutions:

- To drill some holes in the lateral girders and along the deck so that the air flow could circulate through them (in this way reducing lift forces).

- To give a more aerodynamic shape to the transverse section of the deck by adding fairings or deflector vanes along the deck, attached to the girder fascia.

The first option was not favored because of its irreversible nature. The second option was the chosen one; but it was not carried out, because the bridge collapsed five days after the studies were concluded.[4]

Collapse

The wind-induced collapse occurred on November 7, 1940, at 11:00 a.m. (Pacific time), because of a physical phenomenon known as aeroelastic flutter.[1]

From the account of Leonard Coatsworth, a Tacoma News Tribune editor who was the last person to drive on the bridge, he was driving with his dog, Tubby, over the bridge when the bridge started to vibrate violently. Coatsworth was forced to flee his car:

Just as I drove past the towers, the bridge began to sway violently from side to side. Before I realized it, the tilt became so violent that I lost control of the car...I jammed on the brakes and got out, only to be thrown onto my face against the curb...Around me I could hear concrete cracking...The car itself began to slide from side to side of the roadway.

On hands and knees most of the time, I crawled 500 yards (460 m) or more to the towers...My breath was coming in gasps; my knees were raw and bleeding, my hands bruised and swollen from gripping the concrete curb...Toward the last, I risked rising to my feet and running a few yards at a time...Safely back at the toll plaza, I saw the bridge in its final collapse and saw my car plunge into the Narrows.[6]

No human life was lost in the collapse of the bridge. Tubby, a black male cocker spaniel, was the only fatality of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge disaster; he was lost along with Coatsworth's car. Professor Farquharson[7] and a news photographer[8] attempted to rescue Tubby during a lull, but the dog was too terrified to leave the car and bit one of the rescuers. Tubby died when the bridge fell, and neither his body nor the car were ever recovered.[9] Coatsworth had been driving Tubby back to his daughter, who owned the dog. Coatsworth received US $450 for his car and $364.40 in reimbursement for the contents of his car, including Tubby.[10]

Inquiry

Theodore von Kármán, the director of the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory and a world-renowned aerodynamicist, was a member of the board of inquiry into the collapse.[11] He reported that the State of Washington was unable to collect on one of the insurance policies for the bridge because its insurance agent had fraudulently pocketed the insurance premiums. The agent, Hallett R. French, who represented the Merchant's Fire Assurance Company, was charged and tried for grand larceny for withholding the premiums for $800,000 worth of insurance. The bridge, however, was insured by many other policies that covered 80% of the $5.2 million structure's value. Most of these were collected without incident.[12]

On November 28, 1940, the U.S. Navy's Hydrographic Office reported that the remains of the bridge were located at geographical coordinates , at a depth of 180 feet (55 meters).

Film of collapse

The collapse of the bridge was recorded on film by Barney Elliott, owner of a local camera shop. The film shows Leonard Coatsworth leaving the bridge after exiting his car. In 1998, The Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant. This footage is still shown to engineering, architecture, and physics students as a cautionary tale.[13] Elliot's original films of the construction and collapse of the bridge were shot on 16 mm Kodachrome film, but most copies in circulation are in black and white because newsreels of the day copied the film onto 35 mm black-and-white stock.

Commission of the Federal Works Agency

A commission formed by the Federal Works Agency studied the collapse of the bridge. It included Othmar Ammann and Theodore von Kármán. Without drawing any definitive conclusions, the commission explored three possible failure causes:

- Aerodynamic instability by self-induced vibrations in the structure

- Eddy formations that might be periodic in nature

- Random effects of turbulence, that is the random fluctuations in velocity and direction of the wind.

Cause of the collapse

The original Tacoma Narrows Bridge was solidly built, with girders of carbon steel anchored in huge blocks of concrete. Preceding designs typically had open lattice beam trusses underneath the roadbed. This bridge was the first of its type to employ plate girders (pairs of deep I beams) to support the roadbed. With the earlier designs any wind would simply pass through the truss, but in the new design the wind would be diverted above and below the structure. Shortly after construction finished at the end of June (opened to traffic on July 1, 1940), it was discovered that the bridge would sway and buckle dangerously in relatively mild windy conditions that are common for the area, and worse during severe winds. This vibration was transverse, one-half of the central span rising while the other lowered. Drivers would see cars approaching from the other direction rise and fall, riding the violent energy wave through the bridge. However, at that time the mass of the bridge was considered to be sufficient to keep it structurally sound.

The failure of the bridge occurred when a never-before-seen twisting mode occurred, from winds at a mild 40 miles per hour (64 km/h). This is a so-called torsional vibration mode (which is different from the transversal or longitudinal vibration mode), whereby when the left side of the roadway went down, the right side would rise, and vice versa, with the center line of the road remaining still. Specifically, it was the "second" torsional mode, in which the midpoint of the bridge remained motionless while the two halves of the bridge twisted in opposite directions. Two men proved this point by walking along the center line, unaffected by the flapping of the roadway rising and falling to each side. This vibration was caused by aeroelastic fluttering.

Fluttering is a physical phenomenon in which several degrees of freedom of a structure become coupled in an unstable oscillation driven by the wind. This movement inserts energy to the bridge during each cycle so that it neutralizes the natural damping of the structure; the composed system (bridge-fluid) therefore behaves as if it had an effective negative damping (or had positive feedback), leading to an exponentially growing response. In other words, the oscillations increase in amplitude with each cycle because the wind pumps in more energy than the flexing of the structure can dissipate, and finally drives the bridge toward failure due to excessive deflection and stress. The wind speed that causes the beginning of the fluttering phenomenon (when the effective damping becomes zero) is known as the flutter velocity. Fluttering occurs even in low-velocity winds with steady flow. Hence, bridge design must ensure that flutter velocity will be higher than the maximum mean wind speed present at the site.

Eventually, the amplitude of the motion produced by the fluttering increased beyond the strength of a vital part, in this case the suspender cables. Once several cables failed, the weight of the deck transferred to the adjacent cables that broke in turn until almost all of the central deck fell into the water below the span.

Resonance hypothesis

The bridge's spectacular destruction is often used as an object lesson in the necessity to consider both aerodynamics and resonance effects in civil and structural engineering. Billah and Scanlan (1991)[1] reported that in fact, many physics textbooks (for example Resnick et al.[15] and Tipler et al.[16] ) wrongly explain that the cause of the failure of the Tacoma Narrows bridge was mechanical resonance. Resonance is the tendency of a system to oscillate at maximum amplitude at certain frequencies, known as the system's natural frequencies. At these frequencies, even small periodic driving forces can produce large amplitude vibrations, because the system stores vibrational energy. For example, a child using a swing realizes that if the pushes are properly timed, the swing can move with a very large amplitude. The driving force, in this case the agent pushing the swing, exactly replenishes the energy that the system loses if its frequency equals the natural frequency of the system.

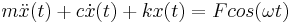

Usually, the approach taken by those physics textbooks is to introduce a first order degree-of-freedom forced oscillator, defined by the second order differential equation

(eq. 1)

(eq. 1)

where  ,

,  and

and  stand for the mass, damping coefficient and stiffness of the linear system and

stand for the mass, damping coefficient and stiffness of the linear system and  and

and  represent the amplitude and the angular frequency of the exciting force. The solution of such ordinary differential equation as a function of time

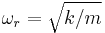

represent the amplitude and the angular frequency of the exciting force. The solution of such ordinary differential equation as a function of time  represents the displacement response of the system (given appropriate initial conditions). In the above system resonance happens when

represents the displacement response of the system (given appropriate initial conditions). In the above system resonance happens when  is approximately

is approximately  , i.e.

, i.e.  is the natural (resonant) frequency of the system. The actual vibration analysis of a more complicated mechanical system—such as an airplane, a building or a bridge—is based on the linearization of the equation of motion for the system, which is a multidimensional version of equation (eq. 1). The analysis requires eigenvalue analysis and thereafter the natural frequencies of the structure are found, together with the so-called degrees of freedom of the system, which are a set of independent displacements and/or rotations that specify completely the displaced or deformed position and orientation of the body or system, i.e., the bridge moves as a (linear) combination of those basic deformed positions.

is the natural (resonant) frequency of the system. The actual vibration analysis of a more complicated mechanical system—such as an airplane, a building or a bridge—is based on the linearization of the equation of motion for the system, which is a multidimensional version of equation (eq. 1). The analysis requires eigenvalue analysis and thereafter the natural frequencies of the structure are found, together with the so-called degrees of freedom of the system, which are a set of independent displacements and/or rotations that specify completely the displaced or deformed position and orientation of the body or system, i.e., the bridge moves as a (linear) combination of those basic deformed positions.

Each structure has natural frequencies. For resonance to occur, it is necessary to have also periodicity in the excitation force. The most tempting candidate of the periodicity in the wind force was assumed to be the so-called vortex shedding. This is because bluff bodies (non-streamlined bodies), like bridge decks, in a fluid stream do shed wakes, whose characteristics depend on the size and shape of the body and the properties of the fluid. These wakes are accompanied by alternating low-pressure vortices on the downwind side of the body (the so-called Von Kármán vortex street). The body will in consequence try to move toward the low-pressure zone, in an oscillating movement called vortex-induced vibration. Eventually, if the frequency of vortex shedding matches the resonance frequency of the structure, the structure will begin to resonate and the structure's movement can become self-sustaining.

The frequency of the vortices in the von Kármán vortex street is called the Strouhal frequency  , and is given by

, and is given by

(eq. 2)

(eq. 2)

Here,  stands for the flow velocity,

stands for the flow velocity,  is a characteristic length of the bluff body and

is a characteristic length of the bluff body and  is the dimensionless Strouhal number, which depends on the body in question. For Reynolds Numbers greater than 1000, the Strouhal number is approximately equal to 0.21. In the case of the Tacoma Narrows,

is the dimensionless Strouhal number, which depends on the body in question. For Reynolds Numbers greater than 1000, the Strouhal number is approximately equal to 0.21. In the case of the Tacoma Narrows,  was approximately 8 feet (2.4 m) and

was approximately 8 feet (2.4 m) and  was 0.20.

was 0.20.

It was thought that the Strouhal frequency was the same one of the natural vibration frequencies of the bridge i.e.  , causing resonance and therefore vortex-induced vibration.

, causing resonance and therefore vortex-induced vibration.

In the case of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, there was no resonance. According to Professor Frederick Burt Farquharson, an engineering professor at the University of Washington and one of the main researchers about the cause of the bridge collapse, the wind was steady at 42 miles per hour (68 km/h) and the frequency of the destructive mode was 12 cycles/minute (0.2 Hz).[17] This frequency was neither a natural mode of the isolated structure nor the frequency of blunt-body vortex shedding of the bridge at that wind speed (which was approximately 1 Hz). It can be concluded therefore that the vortex shedding was not the cause of the bridge collapse. The event can be understood only while considering the coupled aerodynamic and structural system that requires rigorous mathematical analysis to reveal all the degrees of freedom of the particular structure and the set of design loads imposed.

Note, however, that vortex-induced vibration is a far more complex process that involves both the external wind-initiated forces and internal self-excited forces that lock on to the motion of the structure. During lock-on, the wind forces drive the structure at or near one of its resonance frequencies, but as the amplitude increases this has the effect of changing the local fluid boundary conditions, so that this induces compensating, self-limiting forces, which restrict the motion to relatively benign amplitudes. This is clearly not a linear resonance phenomenon, even if the bluff body has itself linear behaviour, since the exciting force amplitude is a nonlinear force of the structural response.[18]

Origin of the confusion in failure modes

It is not clear what is the original source of the confusion . Billah and Scanlan cite that Lee Edson in his biography of Theodore von Kármán[19] is a source of misinformation: "The culprit in the Tacoma disaster was the Karman vortex Street."

However, the Federal Works Administration report of the investigation (of which von Kármán was part) concluded that

It is very improbable that the resonance with alternating vortices plays an important role in the oscillations of suspension bridges. First, it was found that there is no sharp correlation between wind velocity and oscillation frequency such as is required in case of resonance with vortices whose frequency depends on the wind velocity.[20]

Fate of the collapsed superstructure

Efforts to salvage the bridge began almost immediately after its collapse and continued into May 1943.[21] Two review boards, one appointed by the federal government and one appointed by the state of Washington, concluded that repair of the bridge was impossible, and the entire bridge would have to be dismantled and an entirely new bridge superstructure built.[22] With steel being a valuable commodity because of the involvement of the United States in World War II, steel from the bridge cables and the suspension span was sold as scrap metal to be melted down. The salvage operation cost the state more than was returned from the sale of the material, a net loss of over $350,000.[21]

The cable anchorages, tower pedestals and most of the remaining substructure were relatively undamaged in the collapse, and were reused during construction of the replacement span that opened in 1950. The towers, which supported Gertie's main cables and road deck, suffered major damage at their bases from being deflected twelve feet towards shore as a result of the collapse of the mainspan and the sagging of the sidespans. They were dismantled, and the steel sent to recyclers.

"Preservation" of the collapsed roadway

The underwater remains of the highway deck of the old suspension bridge act as a large artificial reef, and these are listed on the National Register of Historic Places with reference number 92001068.[23][24]

A lesson for history

Othmar Ammann, a leading bridge designer and member of the Federal Works Agency Commission investigating the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, wrote:

The Tacoma Narrows bridge failure has given us invaluable information...It has shown [that] every new structure [that] projects into new fields of magnitude involves new problems for the solution of which neither theory nor practical experience furnish an adequate guide. It is then that we must rely largely on judgement and if, as a result, errors, or failures occur, we must accept them as a price for human progress.[25]

The Bronx Whitestone Bridge, which is of similar design to the 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge, was reinforced shortly after the collapse. Fourteen-foot-high (4.3 m) steel trusses were installed on both sides of the deck in 1943 to weigh down and stiffen the bridge in an effort to reduce oscillation. In 2003, the stiffening trusses were removed and aerodynamic fiberglass fairings were installed along both sides of the road deck.

Replacement bridge

Because of materials and labor shortages as a result of the involvement of the United States in World War II, it took 10 years before a replacement bridge was opened to traffic. This replacement bridge was opened to traffic on October 14, 1950, and is 5,979 feet (1,822 m) long — 40 feet (12 m) longer than Galloping Gertie. The replacement bridge also has more lanes than the original bridge, which only had two traffic lanes, plus shoulders on both sides.

Half a century later, the rebuilt bridge that was completed in 1950 was exceeding its traffic capacity, and a second, parallel suspension bridge was constructed to carry eastbound traffic. The suspension bridge that was completed in 1950 was reconfigured to solely carry westbound traffic. The new parallel bridge opened to traffic in July 2007.

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ a b c d Billah, K.; R. Scanlan (1991). "Resonance, Tacoma Narrows Bridge Failure, and Undergraduate Physics Textbooks" (PDF). American Journal of Physics 59 (2): 118–124. Bibcode 1991AmJPh..59..118B. doi:10.1119/1.16590. http://www.ketchum.org/billah/Billah-Scanlan.pdf.

- ^ Henry Petroski. Engineers of Dreams: Great Bridge Builders and the Spanning of America. New York: Knopf/Random House, 1995.

- ^ Leon S. Moisseiff and Frederick Lienhard. "Suspension Bridges Under the Action of Lateral Forces," with discussion. Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers, No. 98, 1933, pp. 1080–1095, 1096–1141

- ^ a b c Richard Scott. In the Wake of Tacoma: Suspension Bridges and the Quest for Aerodynamic Stability. American Society of Civil Engineers (June 1, 2001) ISBN 0784405425 http://books.google.com/books?id=DnQOzYDJsm8C

- ^ Rita Robison. "Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse." In When Technology Fails, edited by Neil Schlager, pp. 18–190. Detroit: Gale Research, 1994.

- ^ Washington State Department of Transportation (2005). "Tacoma Narrows Bridge: Eyewitness accounts of November 7, 1940". http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/tnbhistory/people/eyewitness.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ "Professor's Analysis". Tacoma Narrows Bridge History. WDOT. http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/TNBhistory/Connections/connections3.htm.

- ^ As told by Clarence C. Murton, head of the Seattle Post Intelligencer Art Dept at the time, and close colleague of the photographer.

- ^ "Tubby Trivia". Tacoma Narrows Bridge History. Washington State Department of Transportation. http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/TNBhistory/tubby.htm.

- ^ "Tacoma Narrows Bridge: Weird Facts". Washington State Department of Transportation. http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/tnbhistory/weirdfacts.htm#4. "Finally, the WSTBA reimbursed Coatsworth for the loss of his car, $450.00. They had already paid him $364.40 for the loss of his car's "contents"."

- ^ Halacy Jr., D. S. (1965). Father of Supersonic Flight: Theodor von Kármán. pp. 119–122.

- ^ "Tacoma Narrows Bridge". University of Washington Special Collections. http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcoll/exhibits/tnb/page5.html. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

- ^ "Weird Facts". Tacoma Narrows Bridge History. Washington State Department of Transportation. http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/TNBhistory/weirdfacts.htm#6. ""The effects of Galloping Gertie's fall lasted long after the catastrophe. Clark Eldridge, who accepted some of the blame for the bridge's failure, learned this first-hand. In late 1941, Eldridge was working for the U.S. Navy on Guam when the United States entered World War II. Soon, the Japanese captured Eldridge. He spent the remainder of the war (three years and nine months) in a prisoner of war camp in Japan. To his amazement, one day a Japanese officer, who had once been a student in America, recognized the bridge engineer. He walked up to Eldridge and said bluntly, 'Tacoma Bridge!'""

- ^ "Big Tacoma Bridge Crashes 190 Feet into Puget Sound. Narrows Span, Third Longest of Type in World, Collapses in Wind. Four Escape Death.". New York Times. November 8, 1940, Friday. "Cracking in a forty-two-mile an hour wind, the $6,400,000 Tacoma narrows Bridge collapsed with a roar today and plunged into the waters of Puget Sound, 190 feet below."

- ^ Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert; Walker, Jearl. Fundamentals of Physics, (Chapters 21-44). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-04474-8.

- ^ Tipler, Paul Allen; Mosca, Gene. Physics for Scientists and Engineers : Volume 1B: Oscillations and Waves; Thermodynamics (Physics for Scientists and Engineers). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0903-1.)

- ^ F. B. Farquharson et al. Aerodynamic stability of suspension bridges with special reference to the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. University of Washington Engineering Experimental Station, Seattle. Bulletin 116. Parts I to V. A series of reports issued since June 1949 to June 1954.

- ^ Billah, K.Y.R. and Scanlan, R. H. "Vortex-Induced Vibration and its Mathematical Modeling: A Bibliography", Report No.SM-89-1. Department of Civil Engineering. Princenton University. April 1989

- ^ Theodore von Karman with Lee Edson. The wind and Beyond.Theodore von Karman: Pioneer in Aviation and Pathfinder in Space. Little Brown and Company, Boston, 1963. Page 213

- ^ Steven Ross, et al. "Tacoma Narrows 1940." In Construction Disasters: Design Failures, Causes, and Prevention. McGraw Hill, 1984, pp. 216–239,.

- ^ a b Tacoma Narrows Bridge Aftermath – A New Beginning: 1940 – 1950

- ^ University of Washington Special Collections

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-01-23. http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natreg/docs/All_Data.html.

- ^ "WSDOT - Tacoma Narrows Bridge: Extreme History". Washington State Department of Transportation. http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/TNBhistory/. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ^ Othmar H. Ammann, Theodore von Kármán and Glenn B. Woodruff. The Failure of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, a report to the administrator. Report ot the Federal Works Agency, Washingthon, 1941

External links

- Color video of the original bridge's construction and collapse with narration

- Physics behind the collapse of the bridge

- failurebydesign.info – physics presentation and resources

- Photos of the bridge and the new span under construction

- Tacoma Narrows Bridge (1940) at Structurae

Historical

- 1940 Narrows Bridge (1940 bridge construction) Washington Sate Department of Transportation

- History of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collection – Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collection More than 152 images and text documenting the infamous collapse in 1940 of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. Also covers Galloping Gertie's creation, subsequent studies involving its aerodynamics, and finally the construction of a second bridge spanning the Narrows.

- The Tacoma Narrows Bridge Disaster, November 1940

- Images of failure

- Information and images of failure

- Official site of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge

- Timeline of the bridges

- Tacoma Narrows Bridge

- Suspended Animation – Failure Magazine (November 2000)

- A film clip of the Tacoma Narrows bridge wobbling and eventually, collapsing is available for free download at the Internet Archive [more]